Grange Estate History: Colonial Insights in the Caribbean

Grange Estates across the Caribbean were plantation-era properties established during British colonial expansion, typically focused on sugar production. These estates included Great Houses, sugar mills, and quarters for enslaved workers, forming the core of local economic and social systems. Through the 17th–19th centuries, they relied on enslaved labour and later wage labour after emancipation. Ownership often changed due to market fluctuations, leading to land fragmentation and new settlement patterns in the 20th century.

Understanding the history of Grange Estates across the Caribbean helps explain how land ownership, plantation systems, and colonial administration shaped today’s cultural and economic landscape. “Grange” was a common estate name during British rule, usually signaling agricultural land tied to sugar, cotton, or livestock operations. The estates left behind records of labor patterns, land consolidation, and transitions from slavery to modern settlement structures.

1. Origins of the Grange Estate Concept

The term “Grange” was adopted by British landowners across colonies during the 17th–19th centuries.

It typically referred to a large tract of land operated as a plantation or agricultural holding.

Many Caribbean islands Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad, and St. Kitts hosted estates named “Grange” because the name resembled English rural properties.

Early Grange Estates were usually granted to military officers, merchants, or planters after land surveys conducted by colonial administrators.

2. Development Under the Plantation Economy

Most Grange Estates became sugar-producing operations during the height of the Caribbean sugar boom.

Records from the 1700s show estate layouts with a Great House, boiling house, cane fields, and accommodation for enslaved laborers.

These estates depended on trans-Atlantic trade routes that supplied equipment and exported raw sugar and molasses.

Production cycles followed the harvest season, and estate managers kept detailed logs to monitor yields and freight shipments.

3. Labor Systems and Social Structure

Enslaved Africans formed the primary workforce until emancipation in the 1830s (Britain) and 1840s (other colonial powers).

Estate rolls recorded labor by field gangs, factory crews, and skilled trades such as carpenters and coopers.

After emancipation, many workers remained on or near the estates due to wage agreements or tenancy arrangements.

Early post-emancipation years brought disputes over wages, land access, and mobility as workers negotiated new rights.

4. Ownership Transitions and Land Fragmentation

Many Grange Estates changed ownership due to debt, crop failures, or shifts in global sugar prices.

Some estates were absorbed into larger plantation groups run by merchant houses in London or Glasgow.

Others were broken into smaller freehold lots during the 20th century as governments encouraged small farming and village settlement.

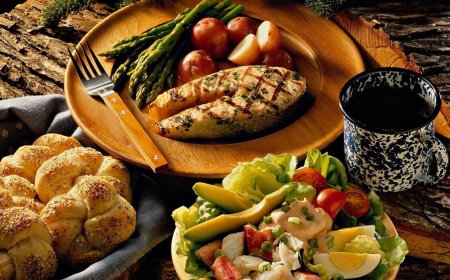

Estate maps from this period show new crop diversification, including bananas, root crops, and small-scale livestock.

5. Role in Colonial Administration

Grange Estates often served as administrative points for census counts, land taxation, and militia coordination.

Estate owners participated in local councils and influenced decisions on infrastructure such as roads, ports, and irrigation works.

Plantation bookkeeping created one of the earliest systematic records of population, production, and land use in the Caribbean.

6. Architecture and Material Heritage

Many surviving Great Houses from Grange Estates feature coral stone or timber construction, with wide verandahs and hipped roofs typical of British-Caribbean design.

Outbuildings such as stables, sugar mills, and cisterns remain among the region’s key historical structures.

Archaeological work at former Grange sites often uncovers domestic items, tools, and pottery connected to daily life on the estates.

7. Post-Colonial Shifts and Modern Use

By the mid-20th century, many Grange estates were repurposed as residential districts, agricultural training centers, or heritage attractions.

Some became government-owned lands supporting reforestation, research farms, or public housing schemes.

Tourism development has adapted select Great Houses into museums, event venues, or boutique accommodations.

Community groups now use former estate lands for cultural festivals, educational programs, and local history research.

8. Why Grange Estates Still Matter Today

They provide insight into early Caribbean economic patterns, including monocrop dependence and export cycles.

Estate records help trace family histories of both plantation owners and descendants of enslaved workers.

Land-use planning in many islands still follows boundaries first set by estates, influencing modern roads and communities.

Understanding these estates supports heritage protection, tourism development, and education on the region’s colonial period.

Grange Estates across the Caribbean represent an important chapter in the region’s colonial past. Their history highlights the evolution of agriculture, labor, administration, and settlement patterns that shaped today’s communities. By studying estate records, surviving structures, and land-use changes, historians gain valuable insight into how the Caribbean moved from plantation economies to independent, diverse societies.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0